Fear and the Fall of Psychedelic Realism

Jim Dine, The Uses of Enchantment. 1992, oil paint, oil stick and charcoal on canvas over wood, 116.84 x 148.59 cm

It was 60 years ago today, when the German born artist Richard Lindner (1901-1978) first exhibited in London at the Robert Fraser Gallery. Opening on Duke Street in 1962 with an exhibition of work by Jean Dubuffet, Fraser’s Gallery quickly became the place to be shown and to be seen. Fraser introduced to British culture the cutting-edge art of Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Jim Dine, and Bridget Riley and lead post-war buttoned-up Britons into the era known as Swinging London.

Graham Keen, Robert Fraser, 1966, photograph, 23.5 cm x 35.5 cm * Behind the elegant Fraser are two photos by Hans Bellmer of his eerie mannekins on display in Fraser’s gallery.

Lindner’s work paralleled this change in culture as he abandoned his dusty-toned domestic narratives of the 1950s for a slyly erotic style that announced a burgeoning European psychedelia. Linder’s fashionable figures were often flat, paper doll-like creations or cubist-inspired machines floating on vibrant backgrounds of orange, purple or teal. Linder’s paintings were flamboyant, voguish and fun.

Left: Richard Lindner, The Visitor, 1953, oil on canvas, 127 x 76 cm Right: Richard Lindner, Solitary III, 1958-62, oil on canvas, 107.2 x 68.8 cm

Lindner escaped Germany in 1933 and eventually emigrated to America. He worked in New York City as commercial illustrator and then began a career as a teacher at Pratt Institute and later Yale University. His art of the 1960s became associated with Pop art but he claimed he was really influenced by New-Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), the Mannheim school of painting from 1925 that sought to depict the matter-of-factness of daily life.

The New Objectivity painters, such as George Grosz and Otto Dix, wanted to capture the harshness of the era of the Weimar Republic and to avoid the overly romantic sentiments of earlier expressionistic artists. By 1930 the movement became aligned with Magical Realism, a similarly minded contemporaneous German art movement whose members sought to paint with precision the uneasy uniqueness of objects, and quickly spread outside of Germany.

Left: George Grosz, Street Scene, 1925, oil on canvas, 81.3 x 61.3 cm Right: Christian Schad, Self Portrait, 1927, oil on canvas, 76 62 cm *Grosz was a New Objectivity painter while Christian Schad was a Magical Realist.

In 1943 with MOMA’s exhibit Americans 1943: Realists and Magic Realists, the curators Alfred Barr and Dorothy Miller defined Magical Realism as realism engaged with fantasy and the interpretation was wide open. Ever since, artists working in a generally fantastical style have been included under this large umbrella term. Magical Realism was not only a prominant art movement of the 20th century but ought to be looked at as a viable alternative to Modernists’ experimentation originating with Picasso and the School of Paris and ending with 1950’s Abstract Expressionism.

Left: Jared French, Murder, 1942 , egg tempera on panel, 43.18 x 36.83 cm Right: Patrick Sullivan, The Fourth Dimension, 1938, oil on canvas, 61.5 x 76.6 in *These works by French and Sullivan appeared in Americans 1943: Realists and Magical Realists.

Magical Realism gave artists who were interested in depicting people, places and things the ability to express themselves in a new way without being trapped in a dead-end realist style. The limits of realism and, by implication, the importance of fantasy to a then-contemporary audience was keenly remarked upon by the film maker Stanley Kubrick after filming A Clockwork Orange (1971): “Telling a story realistically is such a slowpoke and ponderous way to proceed, and it doesn’t fulfill the psychic needs that people have. We sense that there’s more to life and to the universe than realism can possibly deal with.”

The former Beatles member Sir Paul McCartney often frequented Fraser’s gallery and would have known Lindner’s art. As McCartney spearheaded the concept for the Beatles’ eighth studio album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), it was Fraser who insisted on Peter Blake and Jann Haworth, a husband and wife team of artists’ from his gallery’s stable, to design the album’s cover. The album’s cover photo captured the Beatles in fabulously colored and completely fictitious Edwardian military-style band outfits surrounded by over 50 life size cutouts of figures who inspired the Beatles. (Blake referred to the group as a magical crowd). It has been called the best designed album cover ever. With flat cutouts, collage elements, intense circus-like colors and themes, Sgt. Pepper’s bears more than a passing resemblance to Lindner’s aesthetic.

Left: Richard Lindner, Stranger 2, 1958, oil on canvas, 152.5 x 101.5 cm Middle: Blake and Haworth, Sgt. Peppers’ Album Insert , 1967, cardboard, dimensions unknown Left: Peter Blake, On the Balcony, 1955-7, oil on canvas, 121.3 x 90.8 cm * Lindner’s figure has indication of perforation marks, similar to cut-outs on the backs of cereal boxes and appears next to color fields that appear badge-like.

Tellingly, McCartney selected a photograph of Lindner for the album cover, placing Lindner two rows above George Harrison between the comic duo Laurel and Hardy. With his dazzling designs Lindner’s art of the mid-1960s is akin to West Coast psychedelic art, whose rich history is traced back to posters, California music and LSD. Lindner’s bold poly-chromed depictions could best be described as Psychedelic Realism.

Left: Wes Wilson, Beatles’ Last Performance Candlestick Park, 1966, printed material, dimensions unknown Right: Richard Lindner, Rock-Rock, 1966, oil on canvas, 178 x 15.5 2 cm

In June of 1967, The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s album was released. Within three weeks it climbed up the charts to number one, knocking off the Monkees, a band purposefully put together to sound like the Beatles. Having given up touring prior to the release of Sgt. Pepper’s, the Beatles moved into the studio to produce music as they saw fit and to be free of Beatlemania. What they created was a mix of old world British tunes reminiscent of music halls, the vaudeville stage and sideshow performances combined with contemporary melodies and fantastical lyrics. It became the soundtrack to the Summer of Love and changed pop music forever.

Sgt. Pepper’s helped to usher in fantasy and psychedelia to popular culture. Soon thereafter, psychedelic imagery appeared on everything from art posters to soup ads. Once coupled with Madison Avenue advertisers, however, psychedelia was tamed and lost its counter-culture edge.

Left: Richard Avendon, John Lennon, 1967, offset lithograph, 78.8 x 57 cm Right: Campbell’s Soup Ad, 1968, printed material for magazines, dimensions unknown

The easiness, frivolity and love expressed by the Beatles was not to last either. Soon throughout America, France and Britain there was widespread anger and violence. The Rolling Stones’ album Aftermath (1966) presaged this shift in the cultural attitude with darkly subversive songs (such as Under My Thumb, Mother’s Little Helper and Paint it Black) that explored the themes of sex, drugs and hate. By the end of the 1960s psychedelic art was replaced by the psychodramatic.

Richard Lindner, The Street, 1963, oil on canvas, 183 x 183 cm

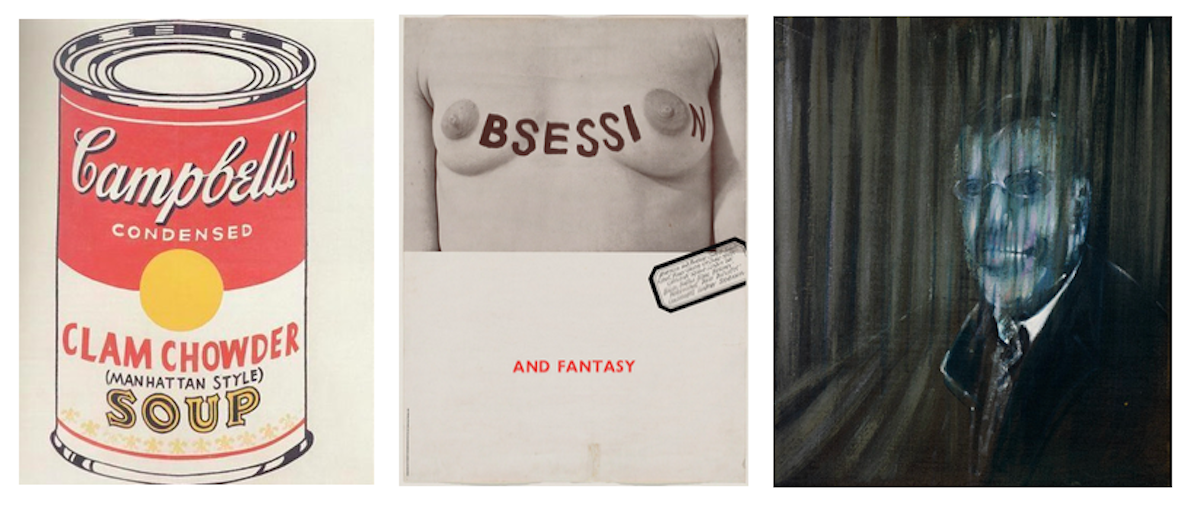

Fraser may have picked up on an uneasiness in the culture early on. With Obsession and Fantasy, a group show in June of 1963, Fraser placed the unsettling photographs of a fetishized mannequin by Hans Bellmer, a grimacing portrayal of a head by Francis Bacon, alongside early Pop works by Peter Blake and Andy Warhol. In exhibiting these works side by side Fraser displayed the tension between bright and dark, a visual equivalent of the moral categories of good and evil.

Left: Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup (Manhattan Clam Chowder), 1962, casein on canvas, 50.8 x 40.6 cm Middle: Robert Brownjohn, Exhibition poster for Obsession and Fantasy, 1963, printed material, dimensions unknown Right: Francis Bacon, Study of a Head, 1953, oil on canvas *Brownjohn was a noted designer that combined formal elements with a pop aesthetic. He famously designed the Rolling Stones Let it Bleed (1969) album cover that featured the song Gimme Shelter, a raucous piece with lyrics of war, rape, fear and destruction which was thought up by Stones’ guitarist Keith Richards as he watched an approaching rainstorm from Robert Fraser’s London flat.

It’s interesting to note that from the start, Pop artists dabbled with dark themes. About the time of Obsession and Fantasy Peter Blake was showing paintings inspired by pro-wrestlers. Blake remarked about his gladiators in tights that “ I loved the theater, the fantasy, and the idea of good versus evil”. Blake’s fighter-performers often appear cartoon-like and are perfect to represent the controlled cartoon violence of wrestling.

At the same time, in 1963, Warhol began his Death and Disaster series, a loosely linked set of 70 canvases in which he silk-screen printed car crashes, the electric chair and race riots. Warhol’s series of embellished press photos, push at the boundaries as to what is acceptable while being haunting and unsettling works of art.

Left: Peter Blake, Irish Lord X, 1963, oil on canvas, 54.5 x 39 cm Right: Andy Warhol, Five Deaths on Orange, 1963, acrylic and silkscreen on linen, 76.6 x 76.6 cm

As Pop artists presented violent subjects they allowed the viewers to safely observe devastation from a distance. Art is different than real life and what occurs on the canvas, the stage or in the written text needs not be enacted on the street. In this way, the so-called theater of violence provides an opportunity for the audience to process pain and sorrow and to not be overcome by fear.

In the early 1970s Lindner explored in Fun City, a series of 12 lithographic prints, the seedy underbelly of New York City. Using his familiar cast of characters (fetishized females and gleefully gazing males), tension is created between the vibrant color palette and themes of implied licentiousness and danger. Compellingly through his carnival aesthetic, Lindner, a New York City resident, endeavored to depict the societal breakdown all around him and to cloak the darkness in color.

Left: Gerard van Honthorst, The Procuress, 1625, oil on canvas, 104 x 71 cm Right: Richard Lindner, Lollipop, early 1970s, lithograph, sheet size 67.3 x 51.2 cm *A side-by-side comparison allows us to see how prostitution has been depicted in paintings, maintaining a similar look and feel for over 300 years. Lindner’s unique contribution was that he treated this familiar subject in the new visual vernacular of a graphic commercial art style.

From the 1960s to the 1970s the homicide rate in New York City more than doubled. There was such an increase in burglaries and robberies that by mid-decade a coalition of public sector unions (including the NYPD) distributed a pamphlet referring to New York City as Fear City and urged tourists not to go out of their hotels after six o’clock at night. Unfortunately, the culture had changed, the magic of the previous decade was gone and Psychedelic Realism came to an end.

Left: Richard Lindner, Fun City, 1971, color lithograph, 60.5 x 51 cm Right: Council of Public Safety,Welcome to Fear City, 1975, printed matter, dimensions unknown