Eve Biddle and The Year of Mary Ann Unger

In the loft, East 3rd Street, New York City, 1975, all black and white photos courtesy Geoffrey Biddle

“[Unger’s] works occupied a territory defined by Eva Hesse and Louise Bourgeois. But the pieces combined a sense of mythic power with a sensitivity to shape that was all their own, achieving a subtlety of expression that belied their monumental scale.” — Roberta Smith, obituary for Mary Ann Unger in The New York Times,

Most of us have experienced moving through life’s routines only to be ambushed by an olfactory prompt that transports us to another place, to a buried memory, to someone special from our past. It could be the scent of a freshly mowed lawn or of Love’s Babysoft or the aroma of pancakes or simmering borscht. For Eve Biddle it is the acrid fumes of welding that spur her fondest childhood memories. Her mother, the sculptor Mary Ann Unger, would take a break from her studio in the family loft on East 3rd Street to join her daughter at the kitchen table for lunch, smelling strongly of the oxyacetylene torch she used in her work, her cotton turtleneck speckled with holes from the torch’s errant sparks. Many photographs by Unger’s husband Geoffrey Biddle are set in the loft and document their intimate life from these days in New York as the 70s flowed into the 80s. Unger’s studio labors were an integrated constant in the household, a world not at all off-limits to her young daughter. Eve Biddle has a clear memory of standing on a stool at the slop sink in the studio washing brushes watching her mother work. “To this day that burning oxyacetylene smell that many dislike is totally associated by me with my family at home. I love that smell, why is that? It’s so funny, I mean it’s not jasmine.”

In the Studio, East 3rd Street, New York City, 1984

This past fall, the Williams College Museum of Art presented a survey of Unger’s work, entitled “To Shape a Moon From Bone,” curated by Horace D. Ballard. While well known in the years before her early death in 1998 at the age of 53, Unger has benefited from this reappraisal. “To Shape a Moon From Bone” is an insightful refresh and sheds light on Unger’s life and work. In a surprising move, Ballard also includes work by Eve Biddle, now 40 and herself an artist, a mother and a co-founder of the Wassaic Project in upstate New York. This dialogue — and its subsequent resumption in “Generation” at Davidson Gallery in New York organized by Ylinka Barotto — introduces a narrative of parents and children, loss, resilience and making art. In the past twelve months, Eve and Geoffrey Biddle have had plenty of impetus to reflect on their early days as a nuclear family, a story he describes in his soon-to-be-published memoir, Rock in a Landslide. The renaissance of Unger’s work in these two exhibitions has been complemented by her inclusion in the Whitney Museum’s “In the Balance: Between Painting and Sculpture 1965-1985” and Westwood Gallery’s show of Bowery artists. Artforum, Frieze and Sculpture Magazine, among others, have all published reviews. As Geoffrey and Eve joke, it has been “The Year of Mary Ann Unger.”

Some say that every New York story is a story of real estate. For artists, who require studios and and are always trying to balance opposing needs for money to pay for space and time to make work, this is particularly true, and the chronicles surrounding domiciles and studios take on particular significance. For this family of three, the East 3rd Street loft where they carved a home from a former industrial building would become a haven. The city had bottomed out in 1975 with its near-bankruptcy. White flight and and the collapse of light industry contributed to buildings being abandoned. At the same time, creative young people were energetically identifying opportunity. Unger’s sleuthing uncovered one in a building that was a “fizzled” urban renewal undertaking by the city, and she was able to score a whole floor (“raw and filthy,” according to Geoffrey) where a factory had once produced infusers, perforated metal balls used to steep tea.

Sanding “Benchmarks,” East 3rd Street, New York City, 1977

Mary Ann Unger and Geoffrey Biddle had met in 1975, working at the offices of Magnum Photo, a pre-internet archive where media outlets and other clients would go to access photographic images. Unger’s expertise was in anthropological and ethnographic images while Biddle’s specialty was the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson. Biddle had recently arrived in New York from Boston. Unger was fresh out of her MFA program at Columbia where her classmates included Don Porcaro and Ursula von Rydingsvard. Both were ready to start something new.

With the loft, they combined households and put their self-reliance to the test. Unger tackled the replastering of the walls in her off-hours and as a duo they cobbled together the basics. As Biddle writes in Rock in a Landslide,

I also learned from Mary Ann’s ingenuity how to stretch our dollars. We scavenged together, picking up boards and wooden food crates from the street to construct kitchen counters. We ducked under a chain-link fence and climbed to the third floor of an abandoned Bowery flophouse to pry tiles off the bathroom walls for our tub enclosure. She was resourceful and willing to break the rules. She pried the discs from the electrical junction boxes we were using and filed them down to use as subway tokens. She tapped into an unmetered gas line to feed a ceiling-mounted space heater. When the utility company found out and made us install a meter, Mary Ann unscrewed it each month and attached our industrial vacuum cleaner to run it backwards before the meter reading. Early in the renovation, while we were still working at the photo library, Mary Ann started using her Dad’s deli slicer to turn five-pound boneless canned hams into packets of sandwich meat. Our coworkers teased us over our unchanging lunch diet, but it saved us forty dollars a week, enough to buy the lumber to frame out a wall, the metal to begin a sculpture armature, or a few hundred-foot rolls of Tri-X film.

It was a hand-to-mouth, seat-of-your-pants existence, but it worked. The loft came with no amenities, or even any interior walls, and they transformed it into a functional live/work space composed of a large studio for Unger by the front windows and a darkroom for Biddle, with the remaining square footage dedicated to domesticity. The building itself offered unpredictable comfort. If the coal-fired heat failed or was unattended to, not only would the building become frigid, the water supply from the tank on the roof would freeze and rob the building of plumbing.

Given her prior travels and exploits, no one was surprised that Unger was unintimidated by life just off the Bowery. Her voyages to remote corners of the world and risky adventures had given her worldliness, inner strength and bravado. She had crossed the North African desert alone in a van and boarded a freighter from Morocco to Ivory Coast as the only passenger and woman. She brought back hammered kitchen utensils from Nepal and a custom-made caftan. As Geoffrey Biddle describes it, “Her large personality expanded mine. I was drawn to her hot flame and how it flared up in unpredictable ways.”

Loft view, East 3rd Street, New York City, 1977

Everyone was surprised, however, when after five years of living together, the couple announced that they were having a baby. Biddle remembers that it hadn’t been an easy decision — children are expensive and can hamstring artistic freedom.

One of Mary Ann’s disillusioned friends told her, “I thought you were too ambitious to have children.” Other friends simply opposed marriage and children. Why get bogged down? There was more important work to do, in Mary Ann’s case to make monumental sculpture, a famously macho niche. She feared that having children would swamp her career, while I saw possibility. I wanted children of my own to raise differently than I’d been, to watch and care for and guide, and to photograph as a way to celebrate those values. Because I was five years younger and a man, my less complicated stance was that we could make art and have a family.

Trim on the fire escape, East 3rd Street, New York City, 1984

Eve Biddle was born in 1982. While her first years were not boilerplate Dr. Spock — in a nine-floor building of artists, she was one of three children — she thrived. She had two parents now working from home with flexible schedules. They joked that she was raised having the two best artist’s assistants in New York! Eve remembers: “You want to make a menorah from scratch? Sure! You’re studying ancient Greece and you want to make a double-headed axe? We can probably figure that out.” Eve was an ever-present companion in her mother’s studio and a frequent focus of her father’s camera. She joined her parents’ dinner parties and impromptu exhibitions of friends’ work in the loft and “didn’t clam up.“ None of it was strange to Eve. “When you are a kid, that is your life so everything is normal. I didn’t have a sense that anything was unusual except maybe in middle school when moms were like, ‘I don’t know if my kid can come for a playdate at your house because your neighborhood is so bad.’ And I was like ‘Oh? Everyone is nice to me. Doesn’t everyone know the names of the homeless people who live on their block?’”

It was a precious time when they had everything: love, passion for art, income streams, a healthy child, a home, a community. In 1985, Unger discovered a lump in her breast. She received a cancer diagnosis shortly afterwards which was followed by a radical mastectomy, then a second and chemotherapy. Three years of remission ensued, but the cancer returned. Over the next thirteen years, it spread in a pattern common to this type of cancer: from breasts to bones to brain. Throughout, she continued to nurture her family, and she embarked on her most ambitious work to date.

Snow on the roof, East 3rd Street, New York City, 1986

Building “Temple,” East 3rd Street, New York City, 1986

Geoffrey writes that

Eve needed our help processing her mother’s illness. From early on, she understood Mary Ann was battling something that could kill her. The question none of us could say out loud was, “When?” Our uncertainty was exaggerated by a tacit agreement not to talk about death, a silence Eve was indoctrinated in and adopted. The inevitable questions came as she became more aware and able to express herself. We presented optimism, emphasizing our unity and the fact that Mary Ann was alive now and could live for many more years. We did our best to be honest but also reassuring about our family stability even in the face of cancer. But each of us was scared, followed by an unwanted shadow…. Eve could sense our worry. She told me years later she brooded over losing both parents and dying young herself…. Never passive, Mary Ann approached illness just as she did money and art, as a challenge to meet with resolve and ingenuity. She decided rage and bitterness were a waste of time and tired her out. Instead, she used art to respond to her cancer. She made a significant shift away from abstraction, geometry, and repetition and began to explore the figure.

1985 marked a turning point in Unger’s life and work. Some critics and curators have divided her work into before- and after-diagnosis periods and noted a “darker vein” in the latter. The redirection they identify was boldly asserted in a project she curated at the Sculpture Center. The twelve-artist show entitled “The Figure as an Image of the Psyche” included work by among others Sydney Blum, Greer Lankton, Scott Richter, Nancy Spero, and Unger. It examined a then-contemporary current where sculptors were utilizing the human figure in an expressionistic way to “confront and transform difficult and sometimes extreme responses and experiences,” as Michael Brenson wrote in his review in the New York Times. He termed the show as a whole something like a “war zone [with] traps, dangers and poisons everywhere,’’ and called Unger’s own Supplicant “overwhelming.” This larger-than-life sculpture, with its thrown-back head and open mouth with reddish tongue protruding, echoes the silently screaming female figure on the left edge of Guernica. But Unger has given the figure four stacked breasts and a pair of meager wings, which, together with its gaping mouth, suggest a monstrous baby bird crying to be fed even as, paradoxically, its own attached breasts are engorged.

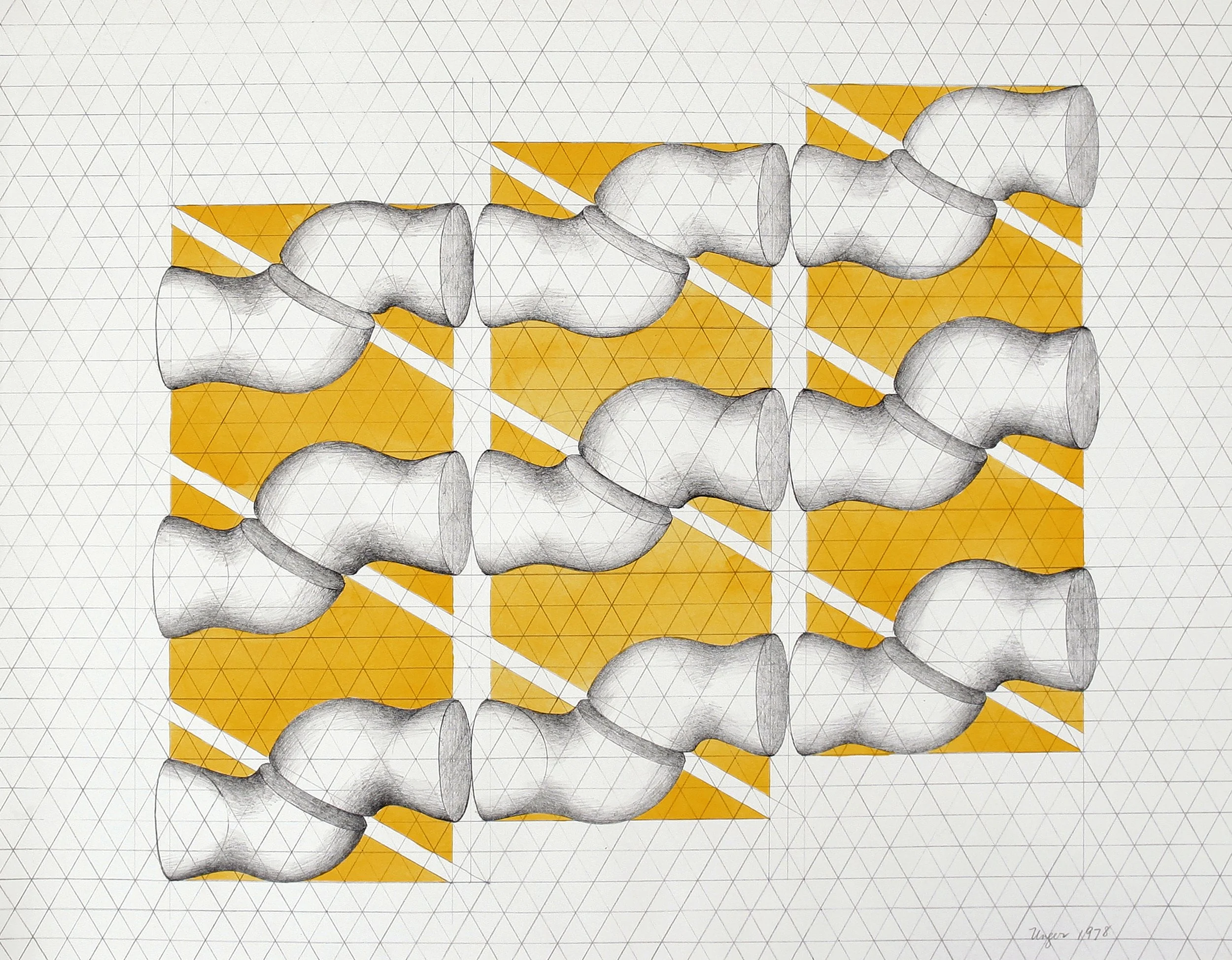

Including Supplicant in “To Shape a Moon From Bone” among such a variety of Unger’s work makes clear what a turning point it was. The extensive two-dimensional works hung in the exhibition exemplify her early interests in grids, patterns and repetition, a focus that was later fleshed out in planar pieces such as Red Vertebrae (1980), borrowed for the exhibition from the Whitney. Similar strategies would emerge in the architectonic and precise pieces with which she garnered numerous percent for art commissions such as Tweed Garden (1985), made from painted plywood, and Wave (1989), made from painted steel. Their interlocking construction does however bridge to the later work, a transition you can see in action in the sequence of Unger’s drawings.

Mary Ann Unger, Untitled (Study for Hexagonal Quintet), 1978, watercolor and pencil on paper, 20.5 x 26.75”, courtesy Williams College Museum of Art and Mary Ann Unger Estate

Mary Ann Unger, Red Vertebrae, 1980. Painted plywood. 5 units, each 22–24 x 12 x 13 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Geoffrey Biddle. © Mary Ann Unger Estate

By the end of the decade Unger’s cancer had returned. In retrospect, it seems that the cancer’s reappearance exerted its impact on her mindset, and, as had been the case when she was first diagnosed, only whetted her appetite for challenge. With the financial support yielded by a Pollock-Krasner Foundation fellowship, an Athena Fellowship and New York Foundation for the Arts grant, she undertook some of her most significant work, much of which Ballard was able to include in his exhibition.

Early morning, Wallkill, New York, 1989

Guardian of Music (completed in 1991), 90 inches tall, is one of the highlights. Lute-like in shape, and also suggestive of the female figure, Guardian of Music was described by Unger in a panel discussion from the Artists on Art series, as a “fertility figure” and its direct inspiration was an African instrument at the Met. Its materials and form of construction — patinated Hydrocal over a steel armature — became Unger’s standard means of constructing the monumental works from this phase.

Mary Ann Unger, Shanks, 1996–97. Hydrocal over steel. 109 x 98 x 34 inches. Williams College Museum of Art, Museum purchase, Karl E. Weston Memorial Fund. © Mary Ann Unger Estate 2022

Shanks (1996-1997) is one of Unger’s last creations and one of the only white ones. It too is created out of Hydrocal-soaked fabric wrapped around a steel armature. It consists of three huge fang-like verticals leaning into and cradled by three loose wall-mounted brackets of the same construction. It epitomizes one of the main themes of the late work, the holder and the held. Eve Biddle describes it in a section of the exhibition catalog “There's nothing holding them together — they're just leaning in an elegant stasis that's really stable. Mom would build the steel armature from gridding two inches square; totally hollow except for a few reinforced rods: an organically shaped, dimensional grid. Then she'd take lengths of cheesecloth, dip them in Hydrocal, and wrap the structure. On top of that, she'd apply more Hydrocal in liquid form, building up the surface.... There's no chiseling. It's all shaping with the hands and the body to get to that surface that references both tenderness and violence."

Ballard’s introduction to the piece (subsequently acquired by Williams College) was pivotal in how the show came to be. Biddle (a Williams College alum herself) had brought him to the premises of the Mary Ann Unger Estate, housed in the reconfigured East 3rd Street loft. He describes exiting the elevator and being “greeted” by the sculpture:

It was installed against the wall between two windows facing the door as sunlight poured through. The work pulsed with such power and self-regard: its tensile forms soaking up the light and refracting it around the space… I must have audibly gasped, because Biddle said, “if you like that, you should see …..” Biddle walked across my vision and disappeared behind a pair of blackout curtains. She pushed them apart to reveal another third of the loft and its “residents.” And that was how I encountered the multiple elements of Unger’s monumental Across the Bering Strait (1992–94}. I was mesmerized. I think I said something grand, like “Wow.” I think I probably tried to follow it up with something more “curatorial,” like “The forms are so powerful and yet not insistent, even as they completely reshape the architecture of the space.” I definitely remember saying, “Oh my god, Eve, what am I even seeing right now?!’”….We spent more than an hour walking around and through Across the Bering Strait.

Mary Ann Unger, Across the Bering Strait, installed at Williams College Museum of Art, 2022, photo KK Kozik

Across the Bering Strait became the centerpiece of “To Shape a Moon From Bone.” Its 30-plus components had first been shown at Trans-Hudson Gallery in Jersey City in 1994. Vivien Rayner of the New York Times described the installation as “a crowd of shapes that are phallic, visceral, even sausage-like.” To me they look like super-scaled chromosomes, some intact and attenuated and some broken and short, some leaning on others that prop them up like a crutch. There is enough rough repetition of shape to provoke imaginings that at some point order had prevailed, that the shapes had once been knitted or woven together but that entropy had had its way.

The placement of the pieces in the installation suggests dolphins arcing higher and higher out of the water, even though the individual forms are more lumpen and trudging than dolphin-sleek. The sculpture ascends like an on-ramp, a stairway to heaven or even the first segment of Hiroshige’s arched bridge. While the title harkens back to the anthropological underpinnings of much of Unger’s work, the forms themselves are ambiguous and reminiscent of many things. They seem stuffed or scatological and their patina has a sepulchral cast. Turning to more contemporary culture, their shapes are like blown up versions of ET’s fingers (released 1982) while their surface texture recalls the figures of the the tannin-cured bog-people discovered in Denmark and Ireland in the 70s and 80s and revealed to the public with great fanfare.

Unger’s own words in a statement at the time specify her allusions to prehistoric migration from Asia across the land bridge of the Bering Strait, and indeed when first exhibited, there was a sound component of Tibetan chants. Closer to home, however, in the heritage of the Ungers and the Biddles themselves there was flight and migration. The Irish Catholics of Unger’s mother’s family escaped desperation in their homeland and her father’s family fled the persecution of Jews in Hungary, just as Geoffrey’s Quaker ancestors became refugees from religious intolerance in England. But Across the Bering Strait also begs a more poetic reading. It seems a metaphor for a brave march to the dark continent of dying. “Mummified“ is an adjective that comes to mind for the wrapped shapes, a process of course meant to prepare a body for its journey to some afterlife.

In addition to selecting such a rich display of Unger’s work, Ballard took steps to contextualize it. He pulled some sidebar examples from the Williams College collection of types of objects that could have inspired Unger — ethnological pieces such as a Yoruba figurine and a Peruvian Vessel and small contemporary sculptural works such as by Maren Hassinger and David Hammons. And he also took a leap by including two- and three-dimensional work by Eve Biddle.

Eve Biddle, New Relics, Bronze Rings, 2020. Ceramic with glaze. 14 x 14 x 1 inches. Photo: Joshua Simpson. Courtesy Eve Biddle Studio

It wasn’t just the mother-daughter relationship that Ballard hoped to emphasize. Strong artist-artist commonalities resonate here. While the selections of Biddle’s work, all from the series entitled New Relics (2020-21), are smaller in scale and different in materials than her mother’s, the general aesthetic seems familiar. Biddle’s three-dimensional work is in ceramic glazed in dark hues similar to Unger’s later choices but what is in great contrast is the intimacy of their making. The imprint of Biddle’s fingers on the clay in the circular and trilobite-shaped ones are vivid records of how they were shaped by Biddle’s hands. Biddle’s work also presents elements of repetition — symmetric openings made by ten fingers or the interlocking elements in Chain.

Both here and in the subsequent Davidson Gallery show a dialog between two artists is presented. While of course Eve Biddle was a witness and a sponge in regards to her mother’s production, what is equally true is that children change parents. She “was never giving her mother career advice,” as she puts it, for instance, but children impact their parents, and can inadvertently impart inspiration and gravitas. That Unger must have considered the effect her inevitable decline and death would have on her young daughter is a given. This conveys new meaning to to pairing of “the holder and the held”’ as the strength and guardianship of a parent and child underwent a reversal.

Installation shot of Generation, Davidson Gallery 2022, photo courtesy Davidson Gallery

In “Generation,” the two women are presented as peers — Eve Biddle at 40 and Mary Ann Unger frozen in time at age 53 are roughly in the same phase of life. Before it opened, Biddle worried that the exhibition would “not feel like two voices,” but in the end it was clearly a conversation. The curating was balanced and each artist was represented by two- and three- dimensional work: sculpture, drawings and watercolor by Unger and sculpture and silk-screen prints by Biddle. Again, all of Biddle’s pieces are listed as part of the New Relics body of work, an amalgam that suggests both looking forward and looking back. Biddle’s glass Spine Impression seems to directly respond to Unger’s various Vertebrae sculptures while Unger’s colossal Talking Stick (1996-7), appearing well-worn by the grip of giant hands, anticipates the finger impressions on Biddle’s ceramic pieces. Biddle states that putting the show together with Ylinka Barotto “was — a surprise to no one but me — very emotional.”

Eve Biddle, New Relics, Spine Impression, 2020, molded glass, 10 x 14 x 6”, photo: Ryan Speth, courtesy Eve Biddle Studio and Davidson Gallery

Mary Ann Unger, Untitled, 1975. Aluminum screen. 29 x 27 x 5 inches, courtesy Mary Ann Unger Estate

When asked to look back, Biddle speaks plainly about her mother, whose death occurred when she was 16. She says that of course there are many times she wished her mother had been alive to see her become an artist herself, marry and have children, yet this year’s exhibitions and the consequent volume of thought and reminiscing have led her to reevaluate. She is about as old as her mother was when she received her cancer diagnosis.

She shared with me recently that a Williams student asked her what is it like to be 40 having lost a parent when young. “It doesn’t go away,” she told me. “The idea of resolution and closure is bullshit. Now I’m 40, she died when I was a teenager. Now I have a totally different relationship with her death. It was different when I got married, different when I had kids. even the happiest moments were also the most stinging in feeling the loss. I am super happy and sad that my mom is not here to see it — the feelings coexist.”

I asked Biddle what she has learned about herself through this year. In reply she tells how in July 2022 Horace Ballard was at Davidson Gallery and was talking about her practice as an artist: “It was the first time someone gave total legitimacy in public for everything I do being part of my practice. The Wassaic Project is part of my art practice. Making sculptures that are abstract, making prints that are representational, supporting other artists, advising my dad, all these things are what I do…. I had conceptually come to this conclusion five to ten years ago but this past year I’ve come around to really owning it.”

Summer Festival at Wassaic Project, Wassaic, New York

Her work has been receiving significant notice — witness the past year — and Wassaic Project where she is co-director celebrates its 15th anniversary this year, having blossomed from its main structure in an abandoned seven-floor grain elevator by the train tracks, into an organization with many fingers in the Wassaic community. It sponsors artist residencies, exhibitions and performances, as well as youth art education, and it even owns a popular bar/restaurant. It is led by young artist-organizers who at this point are mostly parents. Other young families continue to relocate there — often from Brooklyn. Biddle and her husband Joshua Frankel, himself a successful multi-media artist share two children. During COVID they took up full-time residence in the hamlet of Wassaic on a weathered small farm where they have built themselves a comfortable shared studio. Their living room houses two overflowing workspaces — one for each child — and chickens range freely across the grounds.

As Frankel passes through the studio on his way to lunch in the kitchen, I ask him what he thinks about the year’s phenomenon. “I think it is deserved and a long time coming,” he opines, ”and it feels good….The kids can walk up to an object, a sculpture. They can touch what Mary Ann made and there are so many photographs that Geoffrey took. It’s been a family history lesson.” For Geoffrey Biddle, the events of the year have been a culmination of “lots of time and energy honoring Mary Ann as a person and honoring her as an artist.”

Eve Biddle in her Wassaic studio 2023, photo: Jeff Barnett-Winsby, courtesy Eve Biddle Studio

The Year of Mary Ann Unger is soon to wrap up … in a way that goes back to the source. The loft on East 3rd Street continues to play a role in the narration of Mary Ann Unger’s legacy and in the lives of Eve and Geoffrey Biddle. The Mary Ann Unger Estate, managed by Allison Kaufman, was established to support continued management of and access to her work and is there housed. Geoffrey Biddle, who now lives on the west coast and is remarried with three younger daughters, maintains a printing facility for his photos in the loft and there is also an area useable for exhibitions. To that end, William Hathaway a partner in Night Gallery in LA, who grew up in Bar Harbor, Maine exposed to Unger’s work as a friend of the family for many summers, has curated “The Sword in the Stone,” a small show organized around three generations of women, Unger and Eve Biddle and her grandmother Anne Biddle. Hathaway has “chosen work that evokes summers spent with the women and explores memory, myth and illness.” As the last to close of the exhibitions that have brought so much of Mary Ann Unger’s work to the public eye in the last year, it seems fitting that it is located in the loft where the story of it all began.

Postscript

From “Gathering,” in the catalog for “To Shape a Moon From Bone,” Published by Williams College Museum of Art

A Roundtable Conversation with Sarah Montross, senior curator at deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Horace D. Ballard and Eve Biddle

Horace: You are one of the great galvanizers of artistic community, both in the region and in the country. I’m wondering, and this is a huge question, how your parents’ respective practices influence your own sense of being an artist?

Eve: That’s a really big question. In a certain way, we can begin with the question, What is the definition of success in a life, or in an artistic practice? I think, for my parents (though Dad has had the time to grow beyond this in a really wonderful and profound way), thirty years ago, it was kind of MoMA or bust, and that was limited. Their practices and their activities weren’t limited; they did public art and showed with galleries. But I remember reading through Mom’s journals after her death and seeing notes like, “I’m fifty and still no gallery.” You know, brutal. That was a big measure of success. She had very traditional measures of success. In the 1970s and ’80s, there started to be viable alternatives to that model of mainstream success, but I think part of what I was thinking about in my twenties was setting goals I knew I could succeed at and figuring out what could I do. I started making paintings and experimenting after college and realized it wasn’t for me.

My first growing out of that was when I started doing public murals, and those were collaborative with Josh Frankel, my husband, and community based, on the Groundswell model. We did our first murals through New York Cares, working with community and collaboratively with students to form ideas and put their ideas out in the world, and that was really invigorating for me. Bowie Zunino and I started collaborating together, making art first, and doing collaborative art happenings and events while she was still at RISD, back in 2008. Wassaic Project also began around August 2008. And that was great. I was coming out of a season of reading about social practice and about Rick Lowe and Theaster Gates, and then meeting them, and looking at artists who were working in different directions. Rick is an interesting example of that because he has Project Row Houses, but he also has his own practice, and he’s doing all these collaborations, and he’s working with institutions, and then I started thinking about this more and realizing, “Oh, I really can choose my own adventure here.” In 2010, I started working alongside and thinking more with Mom’s work, and then in 2012 or 2014, I was like, “Oh, these aren’t separate at all. That’s just totally make-believe. It’s always all together, and people can engage with whatever they want, but it’s all here, all right here.”

There’s this funny thing happening with the spectrum of work, with Wassaic Project on one end, with its international crop of artists and everything collaboratively minded and really social, and then my own ceramic practice is the opposite of collaborative. It’s me in my studio, alone, with just my hands, at a scale that implies “only I am touching this thing.” If we want to get metaphorical, both practices are about putting a piece of myself out there in the world, whether it is about getting people together or imbuing an object with a part of myself.