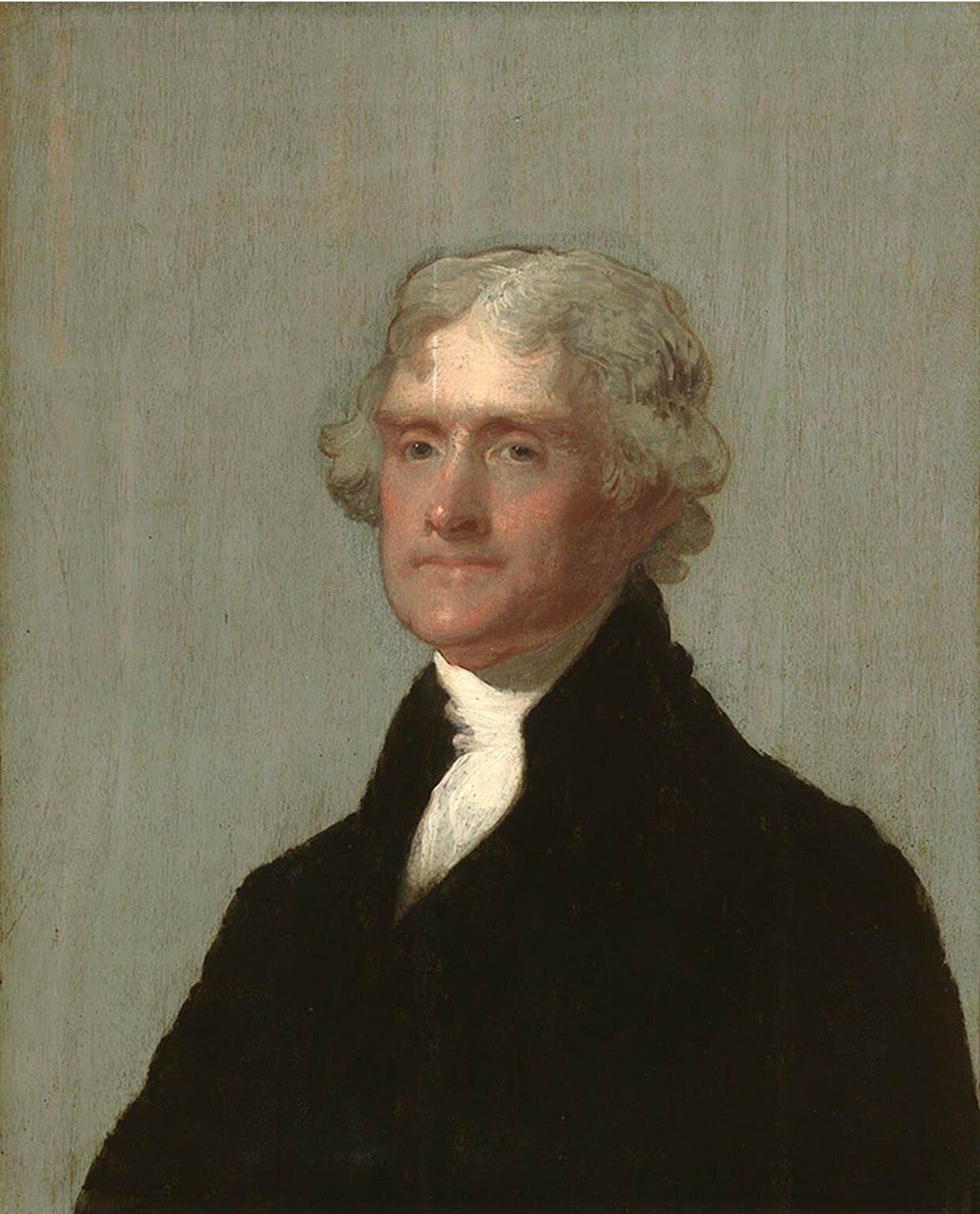

Look: With Dennis Cheaney

The stunning portrait of Thomas Jefferson on a green-grey ground was painted by Gilbert Stuart (1755-1825) and left unfinished in 1805. Long admired by Jefferson it took him at least 15 years to finally receive the painting from the artist. Stuart, by far one of America’s greatest portrait painters, was also a canny businessman. He held onto his unfinished portrait of George Washington (“the Anthenaeum portrait” of 1796 that now hangs at Boston’s MFA) to serve as the model for the 70 copies he painted from it thereby ensuring a steady stream of income throughout his life. Perhaps Stuart intended to do the same with Jefferson’s portrait. In letters to Jefferson, Stuart referred to the unfinished state of the painting as a pretense for a delay in delivery.

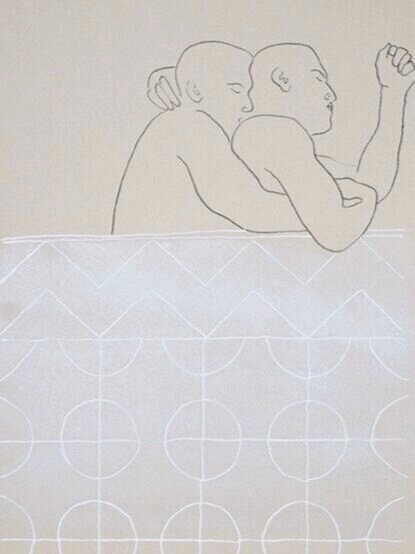

Read: Moby Dick, A Love Story, by Jim Jasper

I first met Herman Melville when I was in high school. I had not come out, would not for a few years, and I had been reading anything that felt like a road map. The authors I discovered, like Burroughs and Genet, were exciting in an underground way. But Melville was breezy, salty, simultaneously half-hidden and completely open, funny and serious. And very sexy. I was certain at the time that the secret of Moby-Dick, that Ishmael and Queequeg were lovers, was something only I had managed to decode. Their love was tangible to me and very reassuring. I read Moby-Dick as a queer love story. Decades later, having left New York for the Berkshires, as Melville did when he was working on Moby-Dick, I decided to make a drawing for each chapter of the book.

Look: The Parcheesi Print, an Etching and a Case Study, by Peter Kirkiles

Five years ago, I purchased a vintage Charles Brand etching press. It had formerly been owned by the late artist, Johnathan Scoville, whose work I greatly admire. I’ve been experimenting and producing works on paper using this press, but this summer I was fortunate to have participated in a week long etching workshop at Crown Point Press in San Fransisco, California. The training explored the beginning to end process of creating copper plate etchings using aquatint and chine collé. I produced five artist proofs of varying finishes and look forward to completing the edition from plates I etched under the guidance of Crown Point’s master printers.

Read: Mrs. Rochester, by Lisa Zeiger

I planned to write, not about Jane Eyre, but about Wide Sargasso Sea, Jean Rhys’s 1966 novel that pulls certain pitch-dark facets of reality barely touched by Charlotte Brontë, not that Brontë was a writer to ward off darkness.

Jean Rhys is my muse, a mentor I never met. Besides reading her books, I pondered her oddities, chronicled in Canadian novelist David Plante’s brief memoir of her in bibulous old age, in Difficult Women. Rhys’s final novel, Wide Sargasso Sea, had long appealed to me as an apologia for my own emotional anarchy, along with her four much earlier novels, each about female trouble, from the insecurity and exploitation of girlhood to the creeping sexual invisibility and disregard of women in middle age.

Look: Bruno Nadalin, It’s Another Door

These drawings are often executed at night, usually after a day spent in vacillation and self-recrimination, in doubt and dawdling, repetition and recitation of the endless sterile story. The sloughed-off skins of the day. The conditions of their conception are meager and poor. The light insufficient, a lingering smell of mold from behind the walls, old wooden planks releasing the heat of the day, the condensation drip drip drip of a thousand air conditioners, tiny ants crawling through the fibers of gray carpeting.