PICTURING DUNCAN HANNAH, Part II

Duncan Hannah, who passed away June 11 of this year, was one in a million. Artist, writer, briefly an actor and always a bon vivant, Hannah lived a big life and chronicled it in his 2018 autobiography Twentieth-Century Boy. It is through these words that we can learn, for instance, about his downtown days in 1970s and 1980s New York and about his connections to Andy Warhol, the Talking Heads, Patti Smith, Tom Verlaine and other famous and infamous characters.

Yet as comprehensive a document as this is, there is of course more to say. In this three-part series, “Picturing Duncan Hannah,” COCOA has set out to create an alternate portrait of Duncan, one sketched by many whose friendships with him were deep and enduring. We are so appreciative of these ten contributors who have given us glimpses into their personal relationships with Duncan — how they met, stories no-one else knows, their grief. Many thanks to Eric Aho, Ellen Berkenblit, Barry Blinderman, Gretchen Carlson and Philip Taaffe, Jeff Joyce, Walter Robinson, Mary Jo Vath, Thomas Woodruff and Geoffrey Young for sharing these recollections. Thank you as well to Sara Cousins and Pierce Kearney and Valorie Fisher and David Cowan for additional images of pieces that were gifts from Duncan.

Read Part One of “Picturing Duncan Hannah” here

Duncan Hannah, Shiny Black Car, 2018, oil on canvas, 12 × 12 inches

* * *

SOME MUSINGS ON DUNCAN

by Thomas Woodruff

Duncan Hannah, Boy and Horse, 1993, oil and sand on canvas, collection and photo Thomas Woodruff

I have three younger brothers, and an older and a younger sister, but Duncan Hannah was my unofficial older brother. I met him in my early 20s on the stairs of the Semaphore Gallery in Soho, where he was having a painting show in the big room. At that moment in time he was a celebrated “art-boy du jour,” who used to punningly describe himself as “King Tot.” After all, he was the star of underground movies, and his dashing photos were in all the coolest magazines. Imagine my disbelief when after our introduction he said,“Oh, you’re Thomas Woodruff, I have a file of your illustrations I am collecting!” I was floored. I was a kid with a scant career, and no one noticed it, but Duncan had. Clearly I was charmed by this unassuming handsome fellow and his idiosyncratic deep knowledge of what he liked, and he had files to prove it. He liked me, and I liked him.

Many of our interests overlapped, and we soon became good buddies, going to shows, concerts, clubs, and films. During the 80s it was cheap and easy to have lots of adventures, and we did. It helped to have good looks and a sprinkling of style. He lived in the West 70s, I lived in the West Village, and most of our art friends were ensconced in the East Village scene. I remember making ardent pilgrimages with Duncan to museums to study the work of some of our heroes : Thomas Dewing, Bouguereau, Vuillard, Blakelock, Hodler, Frederic Church, Casper David Friedrich, Hammershoi (we disagreed on Kitaj and Sickert), and the list goes on. These were clearly not blockbuster artists, but we were into the esoteric. We loved “pictures,” so it was a mission. We traded books. I painted him, he painted me. We were proud of our inner knowledge of our very particular worlds. Duncan reinforced the belief that being a bit peculiar and particular in one’s tastes is truly bohemian…and that it was truly modern to love the present and the past.

Who else could I go with to hear a Ralph Vaughan Williams symphony one night, then go and experience a Cradle of Filth concert another? Duncan could thread that needle and then make a metaphoric cool, slightly goth pocket square to display in his tweed jacket. I loved being a sidekick on the journey.

I didn’t know him as the “Drunken Hannah” persona from his published diary. He was always sober to me. Dunc was also always so calm and confident, and even at times a bit otherworldly. He never worried about money (even though he never really had much). He always believed it would materialize, and it always kind of would. Out of the blue, someone wanted a portrait, or an early painting would be used as a book cover, or Mick Jagger would have just bought two paintings. He was sprinkled with some magic dust that repelled the normal woes that plague other more melancholic mere mortals. O Lucky Man!

He had the gift of totally living in the now while also creating a fictive past to inhabit at the same time. I remember we were sitting outside of my house in Germantown, NY, after I bought it, and he asked about the remnant of a chimney that was bricked up on the inside, “I would get rid of that!” he insisted. “It would make the place better for time travel!”

Duncan Hannah, Portrait of Thomas Woodruff, 1989, oil on panel, collection and photo Thomas Woodruff

Megan was an honorary dreamer in his world as well. They made a coyly curated cottage, filled with quirky curios, and lovely drawings from Bloomsbury draftsmen. They created beautiful bowers, fine-tuning the escapist “Hannah-vision.” Megan’s only competition for his heart was the parade of ghostly starlets who were always coming to visit his studio. Nova Pilbeam, a finely boned British actress with a silly name and a limited Hitchcockian filmography, occupied a special place in his heart. His fixation on her innocent, glowing countenance –- and quirky hats — made her a special muse of his charming cosmology.

Duncan Hannah’s paintings are very carefully hued. To me, he was one of the greatest colorists of our generation. He would prefer to work from black and white reference images. His subjects were carefully chosen to reflect his invented notion of a romantic faux biography. They would then be conjured into truth, rendered in his always surprisingly tangy palettes, filled with the tertiary. For those of you lucky enough to own one, you will know what I mean. On days when one suffers woe, the Hannah on the wall will somehow glow.

Duncan Hannah, Boys on the Beach, 1998, oil and sand on canvas, collection and photo Thomas Woodruff

Duncan Hannah, Lord Greystoke (Tarzan), 2003, oil on canvas, collection and photo Thomas Woodruff

I was lucky to have lunch with Dunc weeks before he left us, meeting first at his new Brooklyn digs, already patinated with floral wallpapers and his lovingly assembled collection. Some of the arrangements were punctuated with the not-so-modern art from his dear friends, but they were thankfully unobtrusive to the atmosphere. The walls were crowded but not clouded. The two floors had the feeling as if he had lived there for decades, and not just a few years.

And then, in his studio parlor, he showed me the hundreds of new canvases, arranged in open cardboard boxes. It was his ongoing series of invented photo magazine covers, all of the same modest size. Each utilized a made up graphic title logo. He then included a painting of an exotic, doe-eyed starlet; or a rockstar; or a poet; and then there would be a circus tiger! Each was more beautiful and curious than the next, imbued with restrained sentimentality. It was his own specialized lexicon of beauty, stacked neatly on the polished floors. Wow. I can’t wait to see them all together up on the walls and to be able to inhabit and imbibe this world…Duncan Hannah's world.

Ours is a world that is greatly diminished by his passing. No more of his glamorous or goofy daily Instagram posts; no more twee sailboats and race cars resting on the ledges; no more of his sly, quicksilver, boyish smiles; no more of his wise insights and wit; no more of being able to live in the orbit of his joy of being. Bon Voyage D.H.

Germantown N.Y., 2022

DUNCAN

by Mary Jo Vath

Duncan Hannah, Love in a Cold Climate, 2007 and Goodbye to Berlin (undated) courtesy Artnet

Duncan and I met when Thomas Woodruff brought him along to my 33rd birthday party. We became friends and mutual admirers, finding ourselves at the same openings and going to see shows together. We traded paintings.

One thing about Duncan that I loved was that he was at once surprising in his tastes — I was astonished to find he was a punk rock aficionado for instance — while also being very, very specific in his preferences.

We were talking one day about his upcoming trip to Spain to meet Megan’s mother. I said something like, that sounds great, and Duncan replied, “Oh, I don’t know…it’s too bad we won’t have time to go to Europe afterwards, it’s so close.” Duncan’s Europe did not include the Iberian Peninsula. He lived in his own bespoke world, and it was a delight to have been invited to visit him there.

New York City, November 2022

Duncan Hannah, Tiger Collage, 2019, birthday present to David Cowan, photo Valorie Fisher

DUNCAN HANNAH

by Geoffrey Young

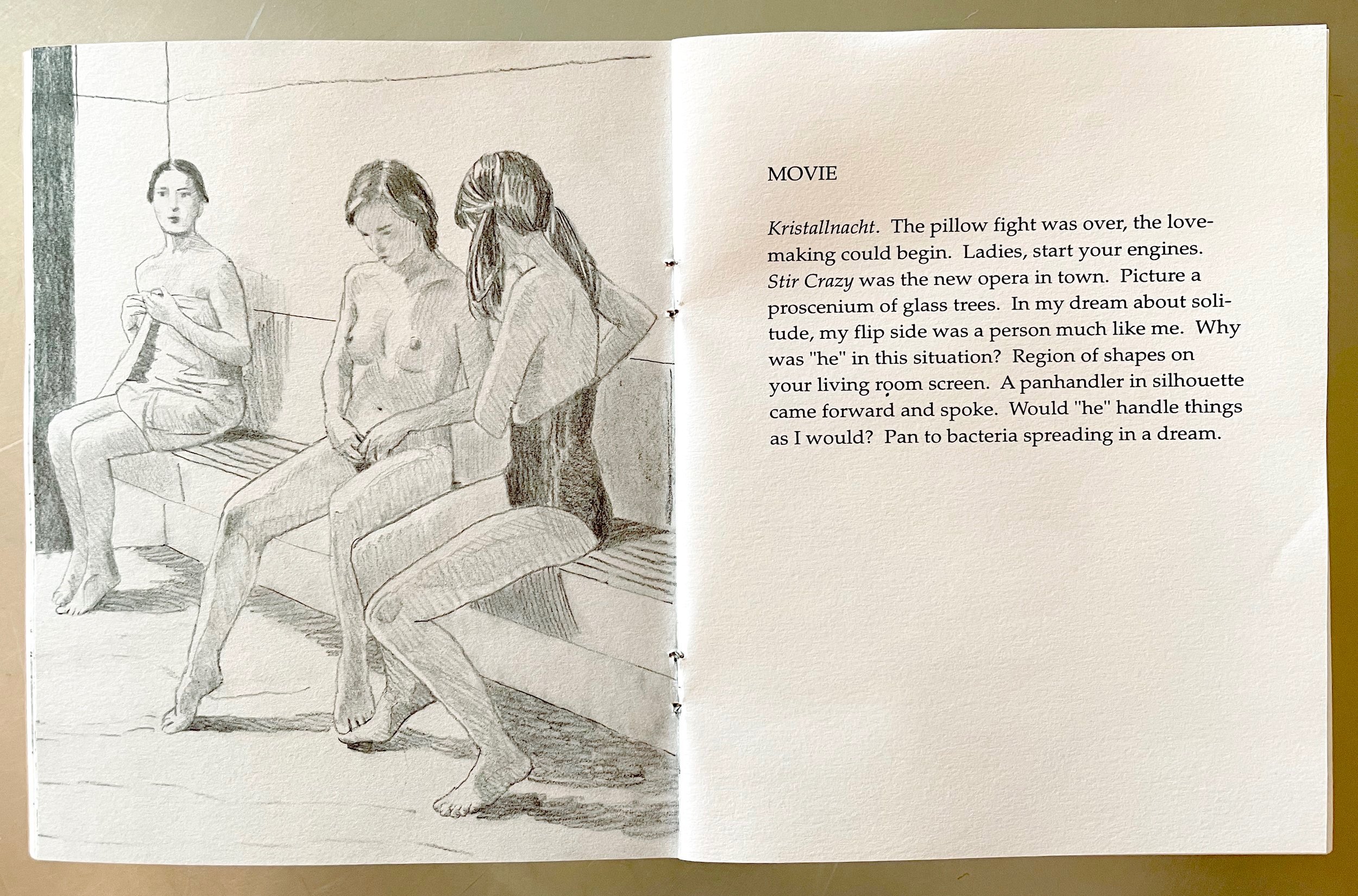

Chapbook published by The Figures, 1996, all photos KK Kozik

It was in Soho, at Barry Blinderman’s gallery, Semaphore, that I first saw Duncan’s work. Don’t remember who urged me up those steps to a second floor space on West Broadway near Prince, but it must have been the mid-80s. Among other paintings, Semaphore was showing Duncan’s portrait of the great tenor saxophonist, Lester Young, upright in a small room. Was Lester sporting his porkpie hat? I haven’t seen the picture since. “Prez” had died in 1959, a jazz legend. I asked the price of the picture — it seemed fair — but I couldn’t afford it.

Then somehow, how? In 1989 Duncan sent me a copy of Duncan Hannah 85, which he described as “an old chestnut.” I looked closely at every picture in this catalog. It gathered his recent paintings and drawings, and provided a smart essay by Carter Ratcliffe. From then on I saw his shows as they happened in New York. Once I opened a gallery in Great Barrington, MA in 1992, I would include Duncan in many a group show over the next twenty-seven years.

In 1996, Duncan made sixteen drawings for Arts & Letters, the name of his collaborative book with Michael Friedman’s prose poems, published by The Figures. That chapbook remains a great juxtaposition of like-minded sensibilities. Terrific to look at, charming to read, and right at the level of feeling. I showed all sixteen drawings at the gallery in the fall of 1996 where they were bought by the collector A. G. Rosen.

Always good to visit Duncan on W. 71st Street. Just inside the entry-way there was usually a stack of completed works leaning against the wall, as well as a work-in-progress on the easel. One of a number of cats over the years would be there, sometimes as a drawing on an easel, most often asleep on a sofa. When my cat Eartha had six kittens in 2013, Duncan and Megan took the dashing young eight-week-old Tarzan off my hands, to be paired with their Jane.

Dunc worked and read every day. He always said yes when I invited him to be in a show. He chose his subjects carefully. His passionate interest in certain periods of the recent past set him apart. Sober and thoughtful, his paintings told sympathetic stories that ranged from childhood nostalgia to youthful beauty to the precarity of a Hopperesque loneliness. Tradition mattered, just as flesh did; old movie stars — or Italian models — back when they were young, were made eternally so, under his brush. It was a pleasure to see the variety of works in his collection, as well — some English, most American — together with art books on tabletops and shelves.

Studious but not pedantic, Duncan had a legendary memory. An impeccable dresser, Duncan took pleasure in draping himself tastefully, as if imported from an earlier time, and was invariably compelling. None of us yet knew that his diaristic memoir, Twentieth-Century Boy, would show up to great acclaim in 2018, making the phrase “riotous youth” so attractive.

In a handwritten note dated Oct. 17th, 1989, after I’d sent him a letter defending his work, he wrote, “Sometimes it feels just like the pool is full of sharks, their irony meters running, and I’m found wanting. I certainly never set out to be an anachronism. I paint for a fictitious audience in my head and hope they’ll understand. Hope they’ll exist! You do. Thanks.”

Great Barrington, Massachusetts, 13 November 2022

Read Part One of “Picturing Duncan Hannah” here

Duncan Hannah, Blues in the Night (Lester Young), 1981, oil on canvas, 40 x 28 inches, photo Barry Blinderman