PICTURING DUNCAN HANNAH, Part I

Duncan Hannah, who passed away June 11 of this year, was one in a million. Artist, writer, briefly an actor and always a bon vivant, Hannah lived a big life and chronicled it in his 2018 autobiographyTwentieth-Century Boy. It is through these words that we can learn, for instance, about his downtown days in 1970s and 1980s New York and about his connections to Andy Warhol, the Talking Heads, Patti Smith, Tom Verlaine and other famous and infamous characters.

Yet as comprehensive a document as this is, there is of course more to say. In this three-part series, “Picturing Duncan Hannah,” COCOA has set out to create an alternate portrait of Duncan, one sketched by many whose friendships with him were deep and enduring. We are so appreciative of these ten contributors who have given us glimpses into their personal relationships with Duncan — how they met, stories no-one else knows, their grief. Many thanks to Eric Aho, Ellen Berkenblit, Barry Blinderman, Gretchen Carlson and Philip Taaffe, Jeff Joyce, Walter Robinson, Mary Jo Vath, Thomas Woodruff and Geoffrey Young for sharing these recollections. Thank you as well to Sara Cousins and Pierce Kearney and Valorie Fisher and David Cowan for additional images of pieces that were gifts from Duncan.

Duncan Hannah, Elsa Reading 2020, oil on canvas, 12 x 12 inches

~PART ONE~

THANKSGIVING

by KK Kozik

Duncan Hannah, Punting on the Cam, 2010. Oil on canvas, 44 x 35 inches. Courtesy Invisible Exports.

November pulls at the heartstrings. Its beauty is stark with light like no other month’s as the sun sits low in a sky newly expanded with the falling of the leaves. Green is gone and the glory of autumn’s colors has sputtered out as year’s-end nears. Even November’s main holidays, Veterans Day and Thanksgiving, are backward-looking. They acknowledge memories both distant and recent while grappling with gratitude for sacrifices made and consequent rewards, together with the sting of our losses.

When the world lost Duncan Hannah this past spring, a deluge of raw social media posts expressed this same duality of emotions. The press too made much of Duncan’s passing — his life was remarkable, after all — but the outpouring of fondness and grief that saturated my feed was impossible to overlook. Moreover, these personal recollections of Duncan seemed important to gather and save, a project that was a natural fit for COCOA, the Journal of Cornwall Contemporary Art, based in the town of Cornwall, Connecticut, where Duncan was a cherished member of the community.

Duncan and I had run in the same circles in New York but had never met until after my family moved to Northwest Connecticut, near Duncan and his wife Megan Wilson’s country home. But I knew of Duncan. In fact I had his phone number in my old black address book. Curator Douglas Blau, who in the 80s had organized two outstanding shows centered around the notion of pictures, as opposed to paintings, had provided me a list of artists to contact. I was wet behind the ears and he felt I needed to enter the conversation and phone Duncan. Douglas was interested in work that went “straight to the content”: that was unimpeded in terms of reading by anything on the surface like, for example, the broken crockery of Julian Schnabel’s contemporaneous paintings. Duncan’s approach, as well as that of Mark Tansey, John Bowman, Tracy Grayson, Troy Brauntuch and Thomas Woodruff, among others, created portals into other worlds. While I came to have friendships with most of the above, I never did call Duncan.

I finally met him around 2007. I can’t say we became close but I was always glad to see him. At one local event he told me I was the best-dressed person there, and coming from him that was really flattering. Another time we talked about rock and roll. On several occasions I ran into Duncan and Megan at Paley’s, a local garden center. We all liked flowers.

I began to see Duncan’s work in person regularly, too. Geoff Young showed him frequently in his gallery in nearby Great Barrington. My favorite Hannah was one I saw there called Green Tights. The sheer emerald tights Duncan painted upon the legs of a topless young woman felt a little naughty and is probably why I remember it so clearly. A tony local inn purchased some of his vintage race car paintings for their tavern walls and whenever there I would examine them stealthily.

Duncan, like very many artists in Cornwall, contributed work to a Cornwall tradition, The Rose Algrant Art Show. Famous or an amateur, Cornwall artists bring work to this summer event each year which benefits local beneficiaries. And here in the Northwest Corner, several of the local libraries maintain lively art programs. Duncan regularly participated — I curated some of his book-cover paintings into an exhibition at one called “Bibliophilia.” This past month the Cornwall Library hosted “The Collected Works of the Late Duncan Hannah,” all pieces selected by his Megan. Among the six towns that make up this region and are increasingly full of large and fancy estates, Cornwall — jokingly referred to as “The People’s Republic of Cornwall” — is considered the most progressive. Its First Selectman (mayor) is also an organic farmer, and much of its social life centers around Cream Hill Lake, an idyllic swimming spot.

Duncan lacked pretension. This surprised many, me included, no doubt because his tweedy, Oxbridge style seemed so bulletproof. It attracted notice, but I don’t believe it was a bid for attention. I think it was just what he authentically liked. Cosmopolitan but still a midwesterner, Duncan was very down to earth. With a life like his maybe he had just seen it all and had nothing to prove and nothing to lose. Those who ventured into his 2018 autobiography Twentieth-Century Boy (titled after a Marc Bolan tune), encountered a judgment-free zone of exploits detailed and names named.

With the book’s publication, suddenly Duncan was everywhere, audiences eager to witness such a distinguished-looking man recount tales of risk and debauchery. Derived from his journals, this compendium starts in Minnesota with Duncan’s young years in art and music and continues through his beginnings in New York which critic Adrian Dannett has described as the “glory years of grungy punkery, 1970-1981, … [the] last great bohemia.” The remembrances his friends have contributed below will tell you much about this time.

Duncan’s days in Cornwall, although falling outside the scope of Twentieth-Century Boy, are interesting on their own. By the early 2000s Cornwall was coalescing into its own scene, as tiny a place as it is (it’s not unusual for its elementary school classes to consist of two or three students per year). By the time I arrived in the area, the community had come to include Glenn O’Brien and Robert Becker, writers from Warhol’s magazine Interview, writers and staff from Artnet and the New Yorker, prominent gallerists, and artists including Carl D’Alvia and the late Jackie Saccoccio, Robert Andrew Parker, Tim Prentice, James Nares, Stephen Maine and Gelah Penn, Carroll Dunham and Laurie Simmons, and Philip Taaffe, to name a few.

Duncan Hannah, Swing, wedding present for Sara Cousins and Pierce Kearney, approximately 1999, etching, 11 x 14 inches

Upon Duncan’s passing, The New York Times printed an obituary that summarized noteworthy episodes of his life and it is worth reading. What is gathered here is different. It is meant as a tribute to Duncan Hannah and the relationships he created with his friends and colleagues and community. I have organized these anecdotes in rough chronological order. Many thanks to all the contributors for sharing their memories, stories and photos of Duncan and of his work. He gave so much of it to his friends. It was a legendary generosity.

Sharon, Connecticut, November 2022

DEAR DUNCAN

by Ellen Berkenblit

Duncan Hannah and Debbie Harry in Amos Poe’s 1976 “Unmade Beds,” photo credit: Fernando Natalici

In 1976, when I was 18 yrs old, I moved into the East Village from northern Westchester to start classes as a freshman at Cooper Union, and on the evening of that first day I went to see Amos Poe’s Unmade Beds at the Millennium Theater. The Millennium was an extremely small movie theater on the Bowery. A friend of mine told me not to go there at night because the Bowery was deserted and dangerous — but I needed to see that movie and the documentary Blank Generation was also on the double-bill.

And there was Duncan Hannah. Not in person — but there he was in all of his insane handsomeness, in celluloid, projected onto the silver(ish) screen. Gorgeous Duncan.

It was about four years later that I actually saw Duncan in person. It was at an opening and I shyly introduced myself. He was so cool, I doubted he would be open to talking to me, but…we liked each other immediately! We had lots to talk about! We both were painters! We both loved Laura Nyro! And from that moment on, we were great friends. Really, really great friends. When Duncan and Megan got together a few years later, I had the good fortune of finding a new beloved friend in Megan. And so it has been for so many good, long years.

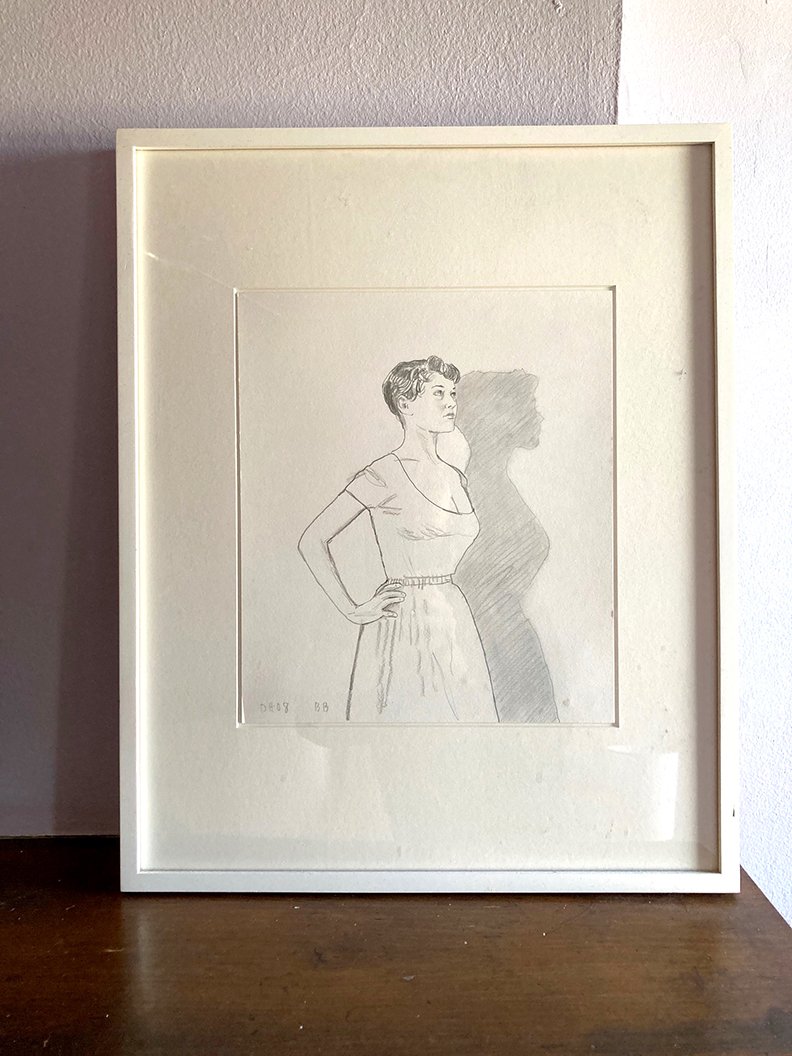

Duncan Hannah, BB (Bridget Bardot), 2008, graphite on paper, 21 x 17”, collection and photo Ellen Berkenblit

I miss Duncan.

Duncan and I "got" each other. We cracked each other up. He was kind and funny and such a great artist.

Brooklyn, November 2022

PICTURING DUNCAN HANNAH

by Barry Blinderman

Duncan in front of his billboard 1984, photo David Forshtay

Duncan Hannah followed his own path, with discipline, a finely tuned vision, and grace. I was privileged throughout the 1980s to present many of the crystalline images he conjured up along the way. Exhibiting his work at Semaphore Gallery in SoHo was one of the highlights of my career in the art world.

My earliest encounter with Duncan’s paintings was in 1981 at the New York/New Wave exhibition, a groundbreaking extravaganza curated by Diego Cortez for the P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center (now MoMA PS1) in Long Island City. There, among works hung floor to ceiling by Robert Mapplethorpe, Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and scores of other artists, he shared a wall of portraits with painter and musician Walter Steding.

Duncan Hannah, Girl With the Flaxen Hair, 1979, named after a song by Debussy, collection and photo Barry Blinderman

Duncan’s head-and-shoulder depictions of Montgomery Clift, Rene Ricard, Ray Johnson, and other luminaries in the arts had a galvanizing intensity. His subjects’ faces were stylized — some positioned against striped backgrounds recalling Modernist abstraction, others set within painted borders, their names hand-lettered or stenciled at the bottom. The portrait of Rene Ricard, with elongated features and nose askew, bore the distinct influence of Modigliani. A few years later Duncan told me how he was once walking along the outside perimeter of Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, stoned on Pernod, when he felt the presence of someone beside him. Duncan turned, and it was Modigliani, wearing a big black hat and a corduroy suit. He looked into the tragic artist’s eyes, which “were just like black marbles.” Modi spoke to him in a wheezing voice, told him to “carry on,” then disappeared.

Duncan Hannah, Portrait of Barry Blinderman, 1984, collection and photo Barry Blinderman

Duncan Hannah, The Dimming of the Day, 1983, portrait of Walter Robinson in front of Van Gogh’s bridge over the Seine,

collection and photo Barry Blinderman

I first met Duncan in the summer of 1982, at his apartment-studio on 71st and Broadway. There were dozens of paintings stacked against the wall and one on his easel. Duncan always painted in oil, as opposed to the quick-drying acrylic nearly all his peers used. The aroma of linseed oil, turpentine, and damar varnish wafted through the air as he showed me canvas after canvas with depictions of theaters, haunted bookstores, graveyards, ships, toy boats, and isolated figures in the woods or standing in front of buildings. There were also portraits of James Joyce playing a guitar, F. Scott Fitzgerald sitting outside the sanitarium where his wife Zelda was recuperating, jazz greats Bill Evans and Lester Young, and a disturbing double-portrait titled Twin Gynecologists, inspired by tabloid fare on the Marcus brothers’ bizarre deaths.

I was floored. Towering bookshelves teeming with art monographs and novels stood in the center of the main room. French New Wave movie posters were hanging on the walls, along with collages by Ray Johnson and Joe Brainard. I spotted the opaque projector he used to project his source materials onto canvas so he could draw the essential outlines in charcoal. He generally composed each painting by combining two or more images scavenged from books and magazines, or black-and-white photos he checked out from the New York Public Library’s Picture Collection. Duncan was a collagist at heart.

Before leaving his studio, I offered Duncan a one-person show for the following winter. Over the course of four solo exhibitions at Semaphore in as many years, curators and collectors alike responded to Duncan’s paintings’ dreamy teleportation to a time of innocence, their Cézannesque brushstrokes, their mystery. Although he was working against the grain of his Neo-Expressionist and media-appropriating contemporaries, the cognoscenti gradually acknowledged his paintings’ criticality, their compelling sense of displacement, their “learned irony,” as described by Times critic John Russell.

Sales of Duncan’s paintings were largely responsible for keeping Semaphore afloat. Responding in a grand gesture, I rented a 20-foot billboard on Houston Street at Broadway to advertise his second solo show. Across from his name, printed in two-foot lettering, was a huge color reproduction of his painting In the Darkness the Game Is Real, which featured Robert Mitchum in a trench coat, from the film noir Out of the Past. William Lieberman, The Metropolitan Museum’s Curator of 20th-Century Art, stopped by to view Duncan’s show. He acquired The Letter, a painting of a young woman sitting at her writing desk, against a diamond-patterned background. Duncan and I were walking on air for weeks — the Met!

At Semaphore, 1985, with Duncan's Ryder's Paintbox, Photo Barry Blinderman

As exciting as that was, the real corker was when art writer Robert Becker brought Mick Jagger into the gallery during Duncan’s last show at Semaphore, in 1986. I really had to make an effort to avoid blurting out something stupid like “Please allow me to introduce myself!” As Jagger sat in the closing room drinking a cup of tea with milk, he said: “Awl take the one with the two little girls on the dawnkey.” They were actually two identically dressed boys with menacing looks, one facing forward, the other backward, but I’m not one to argue. After the show, we shipped off Road Not Taken to Mick’s home on Mustique Island. It took two months to receive his check, signed “Michael P. Jagger.” I kept a xerox of it.

I learned so much from Duncan. An avid reader, filmgoer, and music aficionado, he lent me his copies of Naked Lunch, The Heart of the Matter, and The Maltese Falcon. He took me to see Pandora’s Box and Diary of a Young Girl, starring the bob-coiffed icon Louise Brooks. He made me mix tapes of The Smiths, Cocteau Twins, The Sundays. We flew out to San Francisco, where he introduced me to City Lights Bookstore and Harvey’s bar in the Castro. We managed to survive a hike on the rocky cliffs overlooking Nevada City while tripping on MDA, then drove down Route 1 in the pouring rain, through scary hairpin turns, with no guardrails between us and the Pacific. Hanging out with Duncan was a never-ending adventure, a real rollercoaster ride.

Duncan Hannah, postcard from Paris, photo Barry Blinderman

Duncan died on my 70th birthday, on June 11th, so I was hit doubly hard. He was 69, way too young. I can picture him standing at his easel beside Modigliani, Balthus, Edward Hopper, Walter Sickert, and other artists from his list of Immortals.

Los Angelesen, California, November 2022

DUNCAN

by Walter Robinson

Walter Robinson beneath his portrait by Duncan Hannah, photo Barry Blinderman

I only met Duncan Hannah in 1984, when he was installing his show at Barry Blinderman’s gallery on West Broadway in SoHo. He was sitting on the floor, drunk, not that I noticed especially, being a little high myself. We chatted a bit, and then he said, “OK you can go now.” So we were friends. After Duncan died — he had a heart attack, while in bed watching a French movie, a good way to go, though way too soon — I listened again to his memoir, Twentieth-Century Boy: Notebooks of the Seventies (2018), which he reads himself on Audible. It’s an uncanny experience, hearing his voice — wry, knowing, confidential, happy — and wanting to phone him up with questions. What was it like, I’d wonder, to have everyone tell you that you were beautiful?

Duncan’s book turned out to be a literary achievement, not bad for someone who didn’t have much of a profile as a writer. In the journals he had kept since he was a teen, Duncan had made lists of his artistic enthusiasms, of new books, new record albums, new movies and new art, resulting in an autobiography almost materially rooted in the specifics of its cultural moment. It’s also a coming-of-age story, an adventure where the narrator seeks out the touchstones of his desire, meeting many of his idols. And last but not least Duncan’s story is filled with romance. It’s a chronicle of 1970s New York, that short-lived libertine time bookended by the Summer of Love and the HIV epidemic.

Walter and Duncan traded bunny paintings: Walter’s on the top and on the bottom Duncan’s “Lord Byron.” Courtesy Walter Robinson

The central contradiction of Duncan’s art has always been why an artist with such a deep love for all things bohemian would embrace an illustrative style that seems so unremarkable. Deft but conventional, it wants to look good without making a big deal about it. It’s the subject that matters, not some artistic quest for novelty. I’m thinking here of his love for classic European film stars, for period sports cars and automobiles, and especially his series of Pelican paperback covers, which double down on high culture as a nostalgic fetish. For painters like Duncan, I like to think, the point is not an embrace of strangeness for its own sake, but rather an authentic admiration for all the emblems of free-thinking bohemia. It’s his way of becoming a part of that legendary glamour.

NYC, 11-3-2022

DH drawing given to Walter Robinson. Appears to be a study for “Girl with the Flaxen Hair” above. Collection and photo Walter Robinson