Splendid Isolation: Nietzsche At Sils Maria

“I am a forest, and a night of dark trees: but he who is not afraid of my darkness, will find banks full of roses under my cypresses.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra

Peter Cusack, Splendid Isolation, 2019, Pastel, 18 x 24 in

Nature is a most unnatural subject for me to write about. I find country pleasures at best a pain, at worst a phobic encounter with elements emphatically not mine. Wide open spaces, bristly woods, lakes and ponds that lead nowhere but to the bottom, and houses on isolated acreage bring on dread.

My last long stay two Christmases ago in a rarefied japoniste cabin in the Connecticut woods inspired me to listen to podcasts and watch documentaries, not about Transcendentalist nature-lovers Thoreau or Emerson but the darker spirits of Nietzsche and Foucault. The latter philosopher was pitch dark as John McCain’s maxim. Foucault’s life, particularly his childhood, was a shock corridor that put me in mind of Joseph Conrad’s immortal exhortation in Lord Jim, “In the destructive element immerse.”

Nietzsche exulted, in both his life and his writings, in icy alpine landscapes that were mirrored by the one I was lodged in for a fortnight: the snows of Litchfield County with a dear old friend but no cigarettes. I was there to quit; withdrawal made me take to my bed. In a sub-zero freeze, without the distractions in walking distance—sidewalks, bodegas, hot coffee carts—the cheap city thrills that fuel me through my works and days, I was bereft. Misery loves company. I sought Nietzsche’s.

Safely back in Newark—and Newports—my absorption in Nietzsche during those two weeks has continued over nearly two years. In Nietzsche’s later works, notably

The Gay Science, he wrote in aphorisms complex enough to mesmerize me, brief enough to hold my truncated attention span, but it is as much his life as his writings that rivet me.

I had read large swaths of Nietzsche’s books in the 1970s in college. Now his words are suddenly transparent where once they had been almost opaque. This is because, now knowing something about the extreme solitude in which he chose to live and write, the indomitable life force expressed in his pronouncements seems all the more powerful and poignant considering his thwarted circumstances: chronic illness, rejection in love, near-absolute isolation in dwelling.

From 1881 until 1888 (except for 1882 and his ill-fated interlude and love triangle with Lou-Andreas Salomé and Paul Ree), Nietzsche spent summers in Sils Maria, a village in the 2000-metre high Engadine Valley, surrounded by the Swiss Alps. There was Lake Silvaplana, among others; endless woods, alpine pastures, and precious few inhabitants. Nietzsche wintered during those years in cities throughout Italy—Rome, Genoa, Rapallo,Turin—and in the South of France.

Photo of Sils Maria, 2019, Dave Gruss, Lead Guide, Ryder-Walker Alpine Adventures

During this period, his most productive, Nietzsche completed a book a year, beginning with The Dawn (1881), followed by The Gay Science,Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Beyond Good and Evil, and On the Genealogy of Morality. In 1888, the year he became irretrievably mad, he would finish a mind-boggling five: The Case of Wagner, Twilight of the Idols, The Antichrist, Ecce Homo, and Nietzsche contra Wagner.

Sils’ climate is categorized as “cold sub-polar,” with some of the most extreme seasonal temperature variations found on the planet. In winter, temperatures may drop to below −40 °F, while in summer, typically short, they can exceed 86 °F. With five to seven months of the year below freezing, all moisture in the soil and subsoil frozen solid to depths of many feet. The summer warmth thaws just a few surface feet so that permafrost prevails. The frost-free season is brief—100 days at most—and a freeze can occur at any time of year.

Morbidly sensitive to weather but convinced the cold was bracing to his poor health, Nietzsche suffered in the chill, often tumultuous atmosphere of the high mountains. The snow in Sils did not melt until June, and sometimes fell in July and August, followed by rain, thunderstorms and snow in September. The philosopher nevertheless walked three to four hours—twice a day!—thinking all the while. Nietzsche’s final sojourn in Sils, the summer of 1888, seemed to presage his impending madness, with weather that swung from unseasonable snow to unusual thaw, the latter triggering massive avalanches and floods.

But Nietzsche was in love with, in thrall to Sils’ grandeur, its turquoise lakes, dark forests, and utter silence. At Sils, Nietzsche was above the world he had engaged with contentiously in circles of academe, friendships and frustrated love. The term “splendid isolation,” incidentally, was coined in Nietzsche’s time to mean the British diplomatic practice of avoiding permanent alliances. It fits Nietzsche nicely, for his friendships were peripatetic, ruptured or carried on at the remove of letter-writing.

Famous for his repudiation of the Christian hereafter and its derogation of this world, Nietzsche nevertheless had need of a geographical hereafter himself. The Alps, in their towering, icy purity, were made to be scaled by his New Man, Zarathustra, a being who could not only bear total solitude but enter into it with passion and desire. Thus Spoke Zarathustra is shot through with the leitmotifs of altitude and ice.

But it is Nietzsche’s shelter, his single room on the second floor of the Durisch house in Sils (now the Nietzsche-Haus Museum) that I think of as the taproot of his labors. It was dark, lit by a solitary spirit lamp, and unheated. A period photograph shows broad, bare floorboards with a thin-looking rug; a bed draped in white to one side, a table and chair, and a rather plump sofa in the corner near the one window. Nietzsche proclaimed Sils, and presumably this humble room, to be his “rescue-place...[where] it is quiet in a way I have never before experienced and all the 50 conditions of my poor life are fulfilled...an unexpected and unearned gift.”

Photo of Friedrich Nietzsche’s room in Sils Maria, 2019, Peter Cusack

A month into his first summer at Sils Maria, Nietzsche received (he would have disputed that passive verb) the insight that would permeate every book that followed: that of the Eternal Return. In his final book, Ecce Homo (1888), he remembered the experience, claiming it occurred at an altitude of 6000 feet:

“...the basic conception [of Zarathustra], the idea of the eternal return, the highest formula of affirmation that can possibly be attained, belongs to August of the year 1881...I stopped beside a mighty pyramidal block of stone which reared itself up...It was there that this thought came to me.”

Nietzsche’s biographer, Julian Young, underscores the mystical quality of that moment and its tie in time to the strange stone formation:

“In later years, Nietzsche would fall silent when walking with a companion past the pyramidal stone (thirty minutes’ walk from Sils) as if entering a holy precinct. The arrival of the thought had, for him, the character of a visitation.”

The Nietzsche Stone, near the Lake Silvaplana

Photographer: Armin Kübelbeck, CC-BY-SA, Wikimedia Commons

The concept of eternal return of all the events of one’s life in microscopic detail is only half of Nietzsche’s philosophical equation. Inseparable from it is his doctrine of amor fati, love for one’s fate; indeed, love for every malignant twist in its story. Here is Nietzsche’s New Year’s resolution for 1882, which happens also to begin Book IV of The Gay Science:

“I want to learn more and more how to see what is necessary in things as beautiful. Amor fati: let that be my love from now on! I do not want to wage war against ugliness...Let looking away be my only negation!...someday I want only to be a Yes-sayer!”

In so many words, Nietzsche has told us all we need ever know, without resort to logic, science, religion, or faith. His answer to the ancient, central question of philosophy, “What is the good life?” is breathtakingly simple to comprehend, heartbreakingly hard to enact. It is this: if we accept all our choices and even our catastrophes without quarter, to the extent of wanting to relive every moment of them again, we gain the inestimable gift of life as literature. Every mishap or mistake takes on meaning as though it were an element essential to an overarching plot. Without our errors, there would be no drama—or comedy. Like Oedipus solving the riddle of the Sphinx, Nietzsche solved, or guessed, life’s secret: love and desire what is, for it is your special Providence. “Whatever is, is right,” to quote the hunchbacked yet happy poet, Alexander Pope.

As early as 1873, the period following The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche wrote in a note: “The Greek nature knew how to make use of all the terrible features [of the world]...the use of the harmful for the sake of the useful is idealised in the world view of Heraclitus.”

It is hard to say what Heraclitus, with whom Nietzsche identified, would have made of Nietzsche’s own life, which was nothing if not terrible. His loneliness, ill health, and dreadful luck in love culminated in an eleven-year denouement as the insensate ward, first, of his mother, then, of his sadistic sister, Elisabeth Nietzsche-Forster, who after his death in 1900 mutilated his works into anti-Semitic tracts. Nietzsche himself had abhorred anti-Semitism, writing in 1888 to his friend, the composer Heinrich Koeselitz, “Without Jews there is no immortality.” The distorted adoption of Nietzsche’s ideas by the Nazis were an afterlife torment, an insult to his ghost.

Towards the end, Elisabeth habitually invited visitors to her brother’s bedside to witness his wreckage, an Aristotelian spectacle of pity and fear. The loss of Nietzsche’s mind seems to me like a Promethean punishment shaped specially for him by the Greek gods the philosopher had honored; a unique fit for the hubris of his supreme intelligence.

No deity wants to be outwitted.

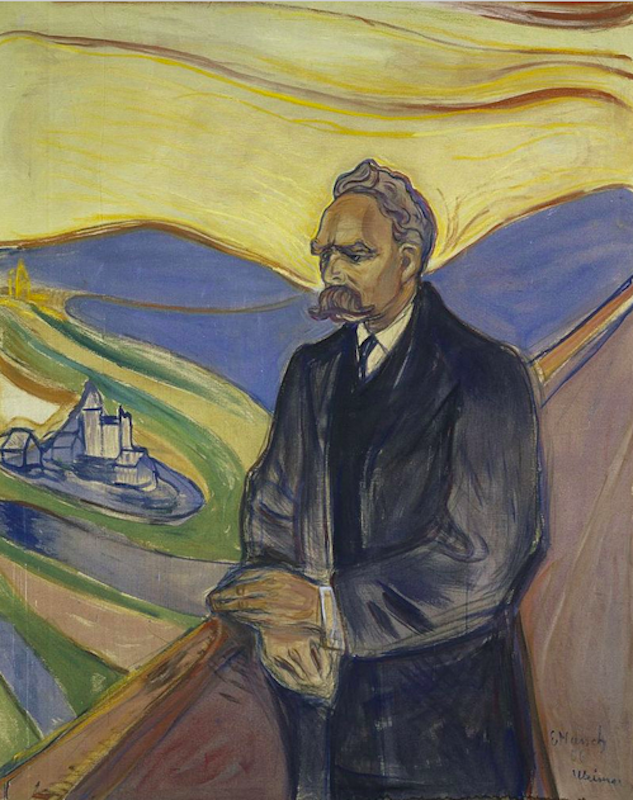

Edvard Munch, Friedrich Nietzsche, 1906, oil on canvas, 79.1 x 62.9 in